de Velde

Ever Meulen

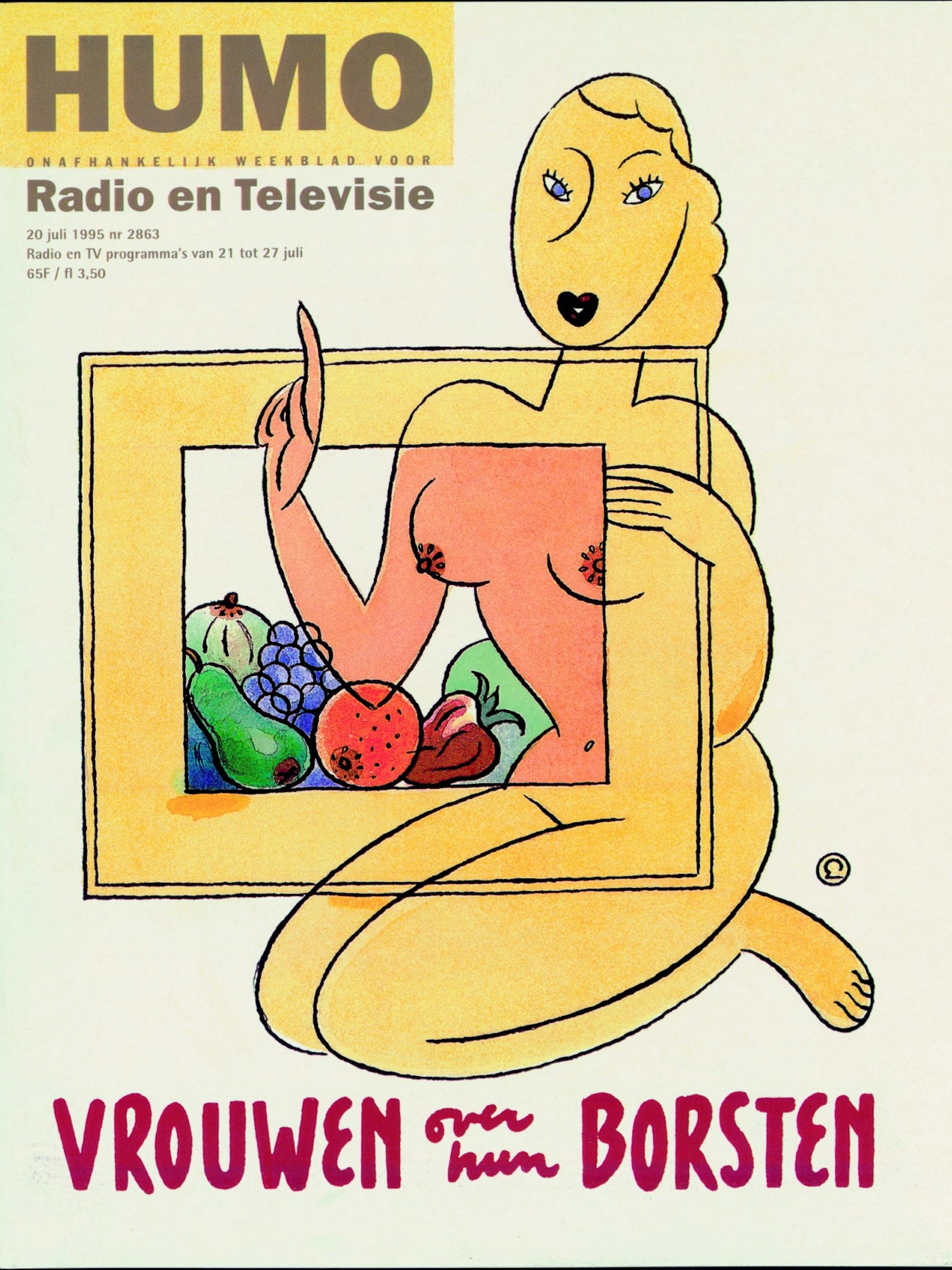

My father had bought Humoradio since time immemorial. It was a magazine to which I willingly devoted my attention from the mid Sixties onwards.

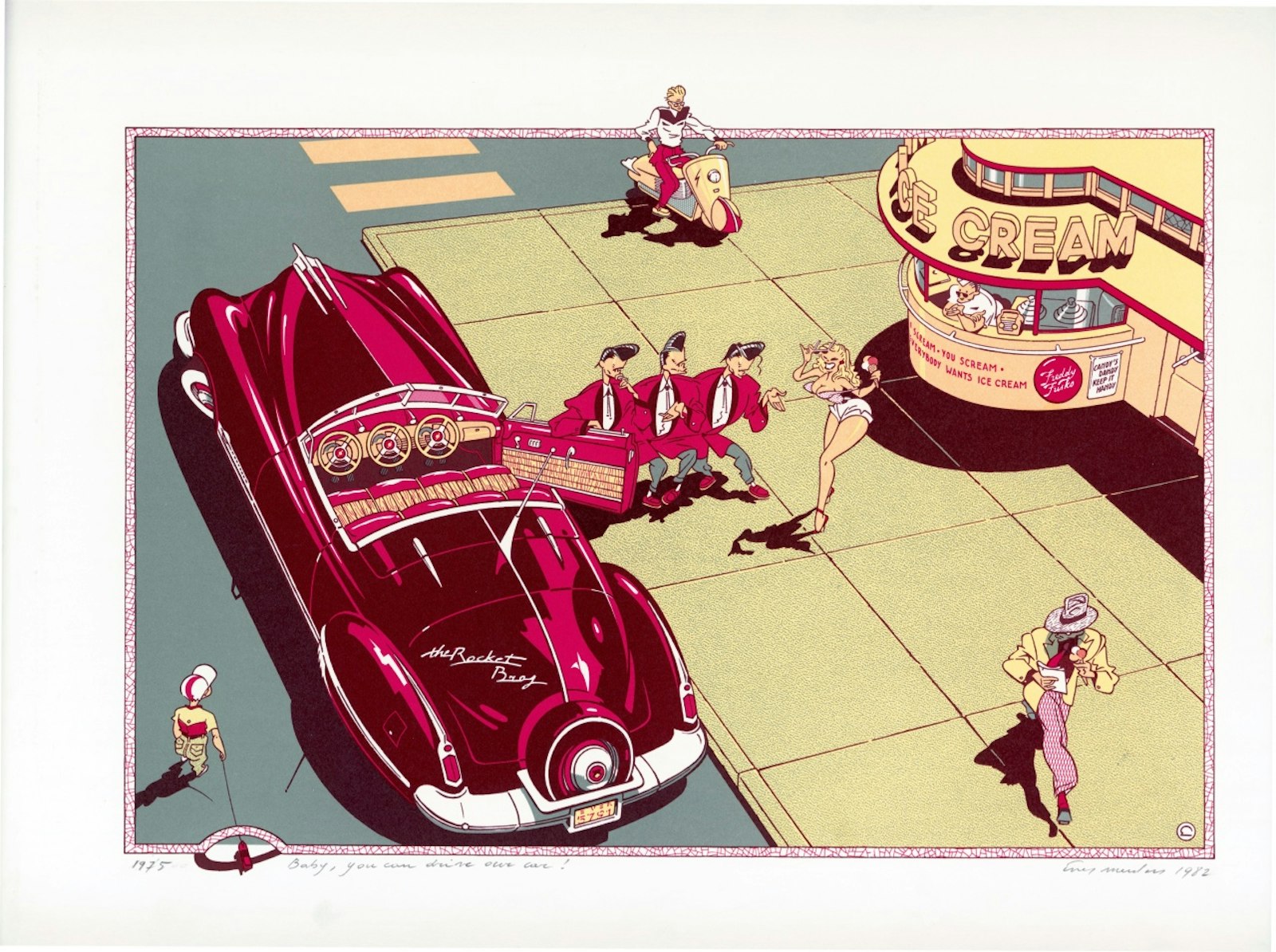

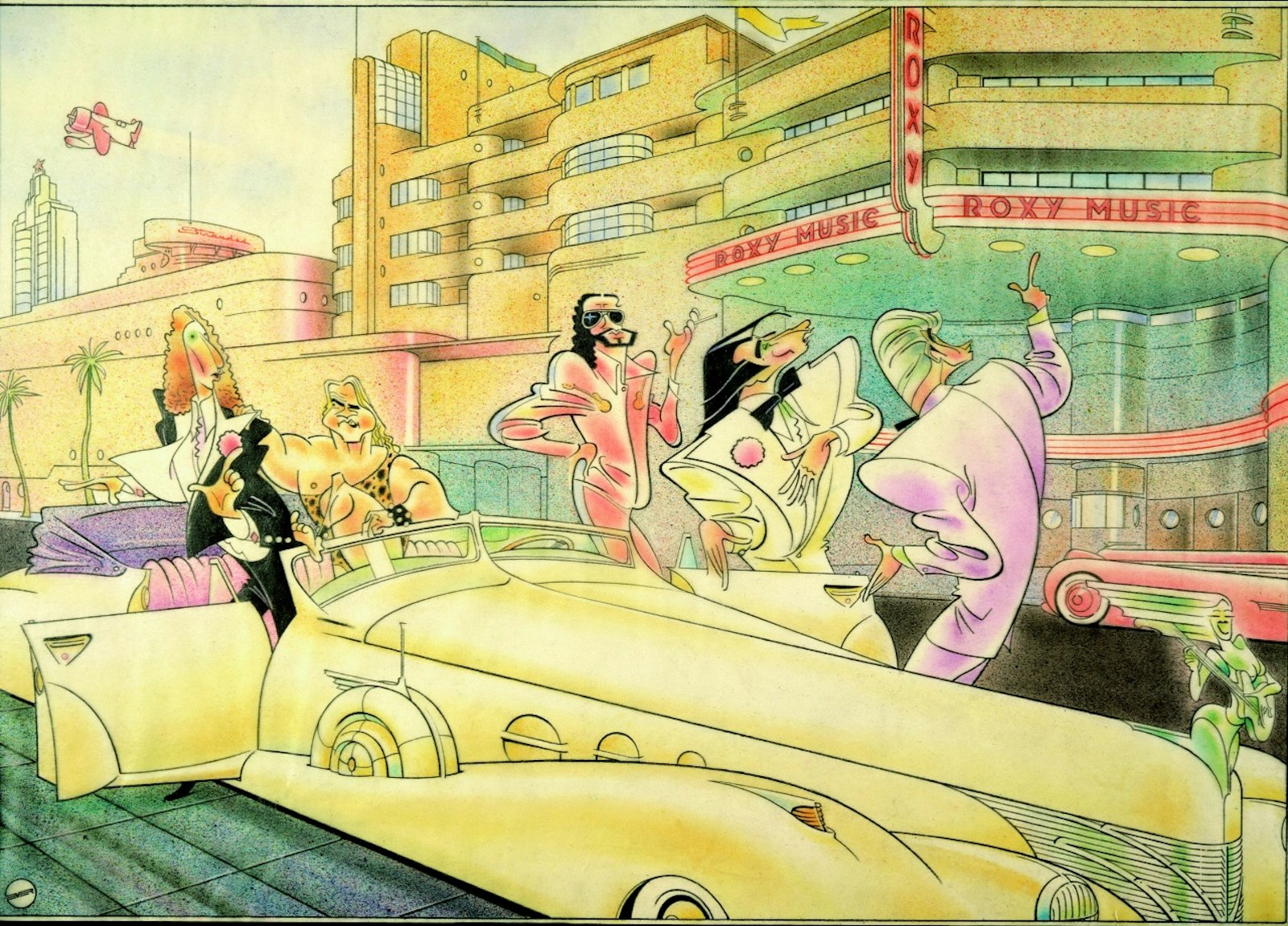

The clear line of rock 'n' roll

The articles about my favourite pop and rock ‘n’ roll groups were written in lively dutch text, funny and to the point. There wasn’t anything like it in the other, banal media. That’s why I liked it. A few years later – in around 1970 – new drawings appeared in the magazine that had meanwhile been rechristened Humo. They particularly appealed to me. They were tailored to my imagination and those of thousands of other young people. I had never seen those types of illustrations before: glitzy cars, pop stars, women with extravagant curves in all the right places, american 1950s architecture, etc. It was love at first sight.

The drawings were beautiful and depicted a world that didn’t exist but one you wished did. I didn’t think about the artist. He existed and that was enough, because he belonged to the editorial department of Humo, the people you looked up to and to whom, at times, you even granted the status of demigod ... well, to a certain extent anyway. Ever Meulen apparently belonged to the merry ‘Humo band’ and no further questions were necessary. Until 12 october 2012, when I met him as a result of the Henry van de Velde Career Award.

The cosy encounter partly took place in his restored Art Deco house in Woluwe-Saint-Lambert where he also has his studio, and partly in the restaurant De Maurice à Olivier a few steps from his house, disguised as a newsagent's but with a superb kitchen that was once awarded a Michelin star. Ever Meulen was born in Kuurne on 12 February 1946.

He must have been jabbed by a pencil as a baby because he published his first drawing in Ons Volkske at the age of seven, and only a year later he scooped up first prize in a drawing competition. Fifty-eight years later he wins our Henry van de Velde Lifetime Achievement Award for the second time. His career has involved success and hard work. His highest accolade was working for Humo. This important event unfolded in 1970. Guy Mortier was interested in Eddy and gave him a chance, a chance that Ever Meulen grabbed with both hands, because he had always wanted to be a comic strip artist, something that was denied him during his studies.

Despite his natural talent he still went to school, at Sint-Lucas in Ghent. There he had to learn how to draw ‘properly’, and his dream of becoming a comic strip artist was banished. Drawing models, with the right proportions, sketching methodically, starting from the primary form of the line: these were the techniques that he worked on and that were meant to turn him into a painter and a ‘proper’ artist. He received this thorough professional training from people including Arno Brys, who was a teacher at the time. Such artistic ambitions were foreign to Eddy. He just wanted to draw men, cars, women and garages with the theme of pop and rock music. Fortunately his studies took him to Ghent and so on his train journeys between Kuurne and Ghent he discovered a spirited companionship whereby Willem Deneckere, Paul Patoor and others made the commuting a pleasurable experience.

It was the artistic ‘Kortrijk gang’ who were all training to be plastic arts teachers and where a certain Jan Hoet studied and Octave Landuyt taught. Ghent sets him on an interesting course, similar to so many from West Flanders, myself included. He became acquainted with the ‘Flemish expressionists’, the ‘New Rococo’ in which Pjeroo Roobjee and Leo Copers were involved, with Raveel’s figuration and with pop art. The young Eddy was particularly influenced by Willem Deneckere. The latter taught him about Hockney and together with Willem Deneckere and Paul Patoor and their wives they left for London in the summer of 1967. It was the era of Swinging London, with the mini skirt, Carnaby Street, the Marquee Club, bowler hats in the City, journalists in Fleet Street and the Black & White Minstrel Show, but also of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, the Spencer Davis Group, and many others.

At the time, pop and rock music were the most striking expressions of youth culture and he, we, were right in the midst of it. Whereas my own participation could best be described as passive, Eddy’s was active and creative. Pop and rock music were his inspiration. At the suggestion of the artistic ‘Kortrijk gang’ he enrolled at La Cambre, though he didn’t even last two months there because it was too focused on Paris and the ‘tableau’, because it was too artistic. That just didn’t suit Eddy. His former love of comic books, guys and cars resurfaced and he turned to Sint-Lukas in Brussels, where Luc Verstraete was teaching. He completed his studies there in 1969.

His friend Luc Guillaume, who produced music under the name of Luc Vankessel, told him to approach Humo, and we all know what happened next. Guy allowed him to first produce a drawing, then a poster and later, to work on and draw the covers. Ever Meulen remained a freelancer, even though he loved to play football with the Humo team. He spent quite some time there. They were also good times at the weekly magazine, with characters like Piet Piryns, Herman De Coninck, Herman Selleslaghs and Marc Didden. As a result of his work for Humo he also became well-known and became involved in the world of advertising in the Netherlands and Paris. He could live as a freelancer, was effective in meeting his deadlines, but above all he drew what he wanted to: cars, architecture with a strange ‘Escher-like perspective’, musicians or things inspired by music and often a pretty lady.

His comic strips: Piet Peuk, Balthazar and De groene steenvreter, all published in Humo.

It is no secret that Ever Meulen has a weakness for cars. They have to be real cars and preferably those large American classics that you can tinker on yourself such as the ageing Oldsmobile that he bought with his very first savings. In 1980 he even moved to an old petrol station, while in his current Art Deco house, which could be a model for some of his architectural drawings, there is a cabinet full of miniature cars and related objects, a silent but unmistakable witness to his love of cars. In 2013 his new book will be launched in which in fact he publishes several drawings that include cars.

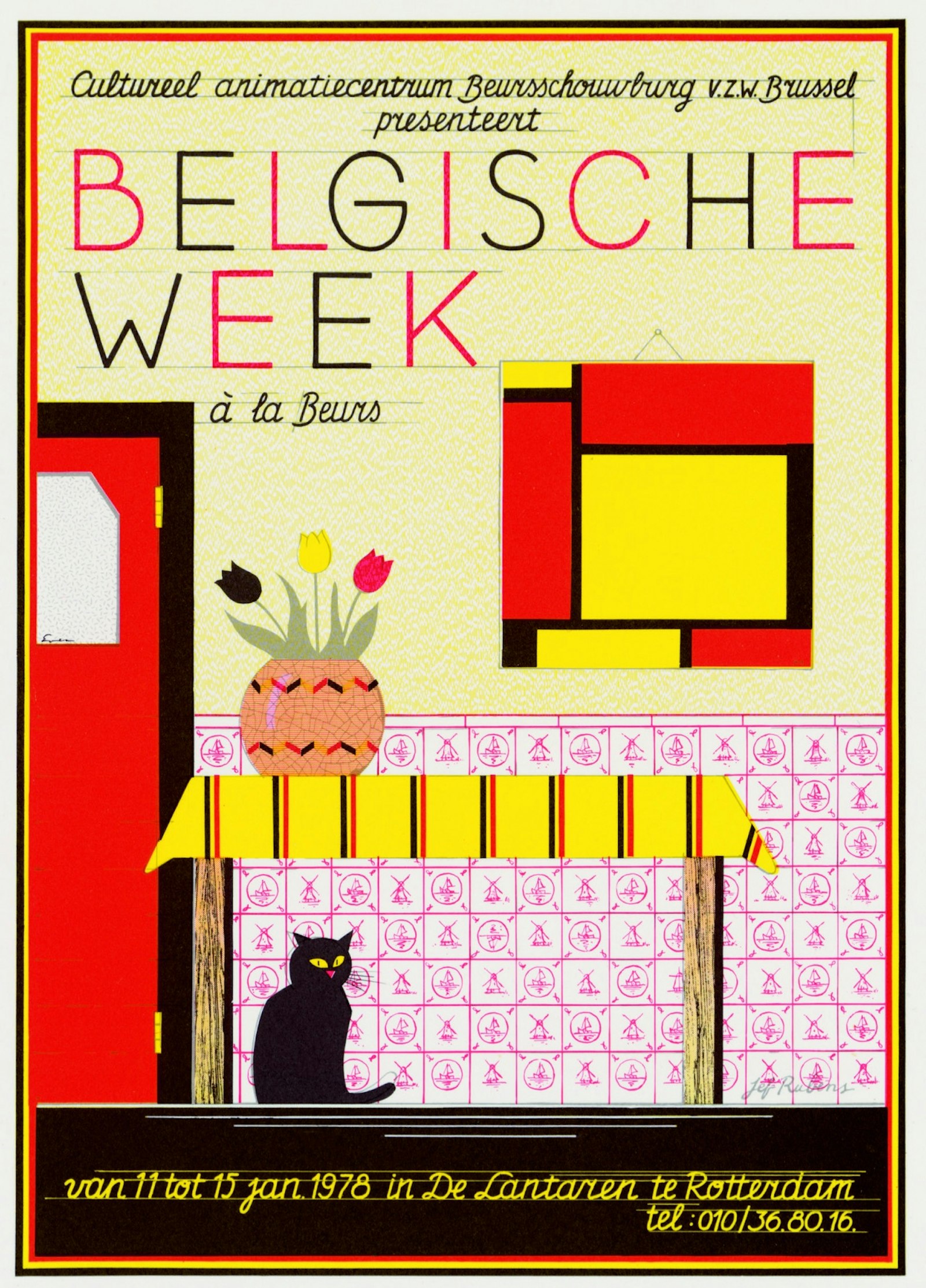

Eddy’s talent as an artist was in great demand. His career started at Humo but expanded to include many other clients, to this very day. He worked for the Dutch music magazine Oor, the Dutch comic strip magazine Tante Leny through Joost Swarte, for the Telex group and for the Kaaitheater, Mallemunt, the Beursschouwburg arts centre, the Brussels underground and other, predominantly cultural organisations. He has drawn Rock Rally posters, designed the trophy for The Golden Owl (De Gouden Uil) literature prize and has had the opportunity of designing stamps.

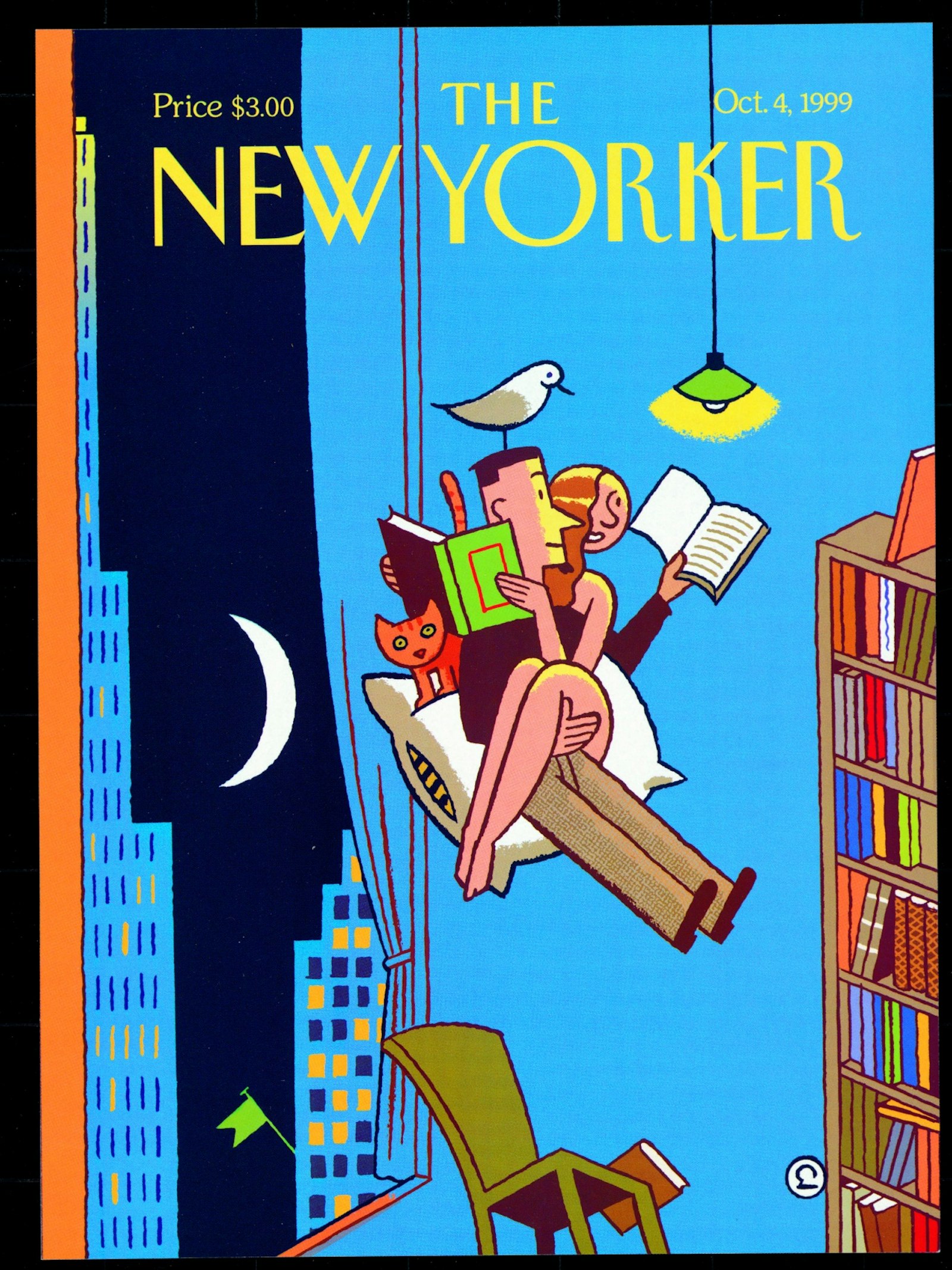

Throughout his career Eddy has been invited to show his work in museums and at exhibitions all over the world and to work for publications such as RAW and The New Yorker. His shining examples of the Ninth Art are Hergé, Franquin, Jijé and Edgar P. Jacobs. It was mainly the latter, with his comic series about Blake & Mortimer, which determined Eddy’s choice to continue drawing his ‘little men’.

He made the acquaintance of Joost Swarte, who became his companion on life’s journey in a special way. One day he suddenly turned up on the doorstep in Brussels to meet Ever Meulen. They appeared to have the same interests in Hergé’s comics and in pop music. Although Joost Swarte had not trained as a draftsman but as an industrial designer, they got on like a house on fire almost immediately. Both are the founding fathers of the ‘clear line’, their style of the Ninth Art. “Joost is incredibly talented, a good analyst and a smart guy”, Eddy told me, “and we are still in touch.” From 1993 to 2009 Ever Meulen taught at Sint-Lucas Ghent, where he led the Illustration Workshop. It made me wonder which upcoming comic strip artists he believes possess the necessary ability. “There are many,” he replies “but I have a preference for Jeroom, Jan Van Der Veken and Peter Willems.”

Meeting Ever Meulen is a pleasant experience. He is still modest and his stories are full of humour. There is a permanent twinkle in his eye, not to be confused with the reflection of the light in his glasses. There is a faint ‘Mona Lisa smile’ on his lips: not mocking but out of pure pleasure. He enjoys life, that’s my impression, and he also maintains a very exceptional perspective on life.

Earlier this year our Design Expert Group, backed by even more external experts, decided that Ever Meulen, Eddy Vermeulen’s pseudonym, would receive the Henry van de Velde Lifetime Achievement Award. An outstanding choice for an outstanding and enlightened professional, I would even dare to call him: an artist.