de Velde

Martine Gyselbrecht

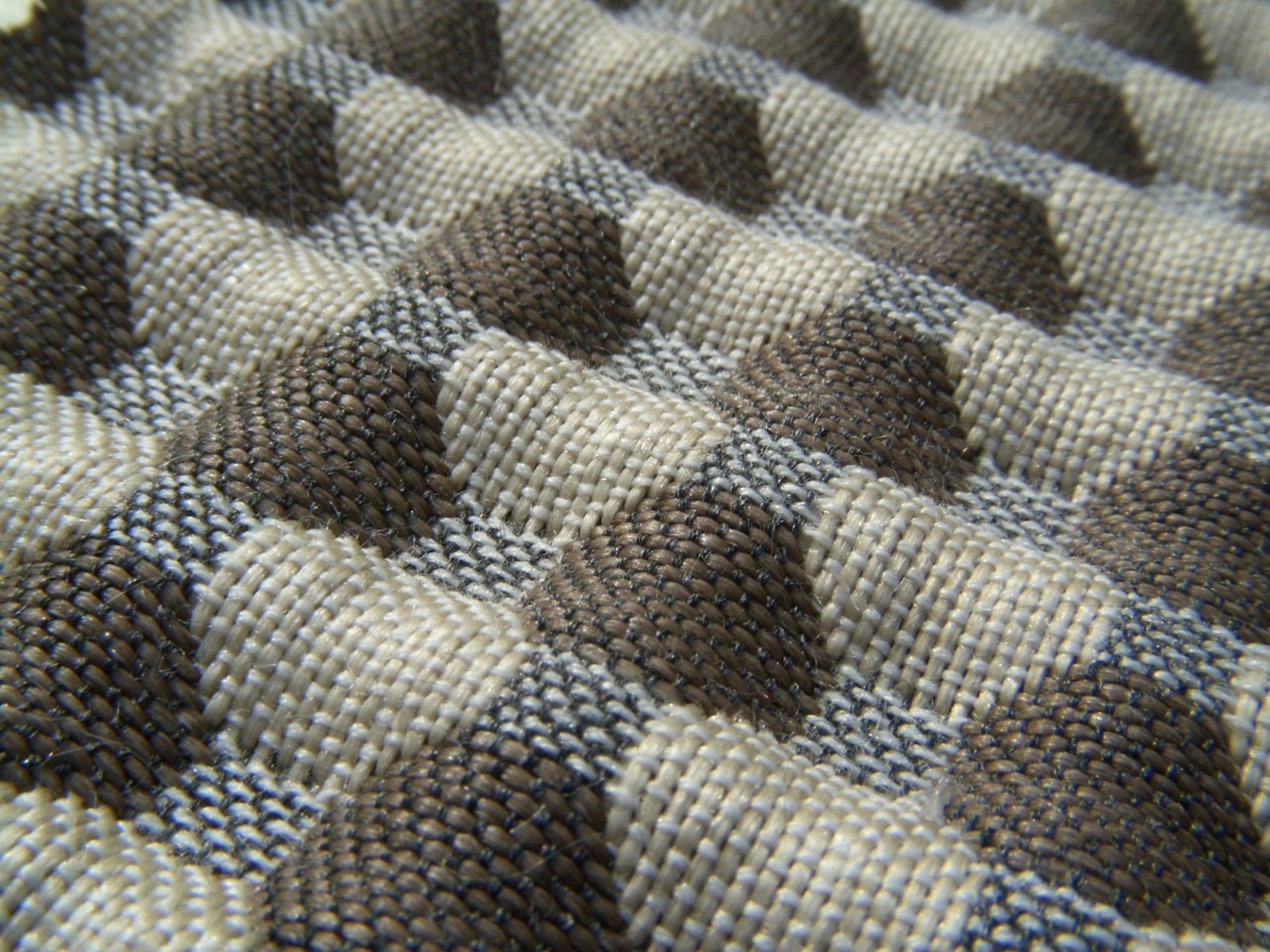

'Fabrics by Martine are specially designed and woven for industry but they still retain the traces of their artisanal origins and approach. The experimental, the artistic and the industrial find a balance. The result is a totally new genre of interior textiles.’ (Provincial Prize for Design 2002, Ghent).

I first met Martine in 1991, the year in which she won an international prize in Kyoto (Japan) for tapestry. In 1992 I invited her to participate with this work in the Milan Triennial, the former world exhibition for design. In 2000 she received the Henry van de Velde Award for Best Product and the Public Award. Nine years later, Martine is now receiving the most prestigious design award in Flanders, Belgium, the Henry van de Velde Career Award.

And very little has really changed. In her home, there are still two looms, the walls are covered with spools of yarn and she still speaks with incredible enthusiasm about textiles. As a girl, she knitted for her dolls, designed clothing and invented fabrics. As a woman, she no longer plays with dolls and she knits less, but she still designs textiles. I asked her where this passion came from and she replied that it has always been there. ‘I’ve always worked with a lot of threads. Crochet, knitting, weaving, sewing, embroidery... in short, everything that involves thread.’

Let’s step back in time, to the 1960s and to the magical year 1968. Martine was just nineteen and conformed perfectly with the image we now have of youth back then, well some youth at least. She moved to the famous Lima Commune in St. Martens-Latem, sick of the consumerism of the ‘Golden Sixties’. Making money was not her goal, but the wellbeing of the planet and nature was. Life in the city annoyed her. She did not want to consume, thus she went to live in nature.

Many years later, she returned to live in a city, in Ghent, having wandered through Merendree, Zomergem and Hansbeke... although she missed the calm, the smell of the countryside and the sound of birdsong. In Merendree she lived on a farm where there were sheep. In an 8-mm movie about the ‘1976 Martine’, we see her watching the sheep shearing, then spinning the wool on a spinning wheel, like those that pricked the fingers of several fairytale princesses, before patiently dying the wool.

The raw materials for her dyes were the flowers, stems, roots and bark of plants and trees. The dye bath consisted of a hot water kettle on a butane gas canister, in which the spun wool was soaked and dyed. This clearly illustrates the artisanal origins of her work. The quantity of wool in Merendree, a loom and weaving classes at the Henry Story School got her off to a good start. At that time, weaving was taught by technicians, who did it perfectly, but worked much ‘too closely’ to the technique itself. This approach almost made Martine give up her training. The following year she was asked to give courses in ‘Colour and Form’, an invitation she readily accepted. This was the start of a decade of exploration and private study, with the aim of sustaining her classes in the most effective way. Those ten years of teaching were also the reason why she only later launched herself as an independent weaver.

In 1989 she decided to work with synthetic yarns for the first time. Previously, these were all ugly, and mainly served as a way to keep prices down. Of course they had their advantages, such as the pleats in Terlenka skirts that never went away, but the benefits were not outweighed by their incredible ugliness. Synthetic yarns are actually chemical emulsions that are sprayed and then remodelled to imitate a ‘natural look’. Fortunately, in the last thirty years there has been a huge and positive evolution in the making of these artificial textile threads. Today, synthetic yarns have properties that natural yarns do not possess. They offer strength, smoothness, elasticity, etc. Think of Lycra. Also not to be underestimated is the new development of ‘smart textiles’ and reused and recyclable materials.

During this period, you had technical threads in metal à la Bekaert, and textile threads for beautiful fabrics. All of them yarn and threads, but they were never mixed. These worlds were completely separate. It was simply not the done thing to mix metal and textile threads. Martine ignored this and began to experiment, although it was far from easy because metal thread was not for sale. She was therefore obliged to buy electro-magnets, from which she extracted the copper wire with which to weave. She also had to make paper thread herself, because this did not exist. She experimented with every possible material, from basket willow to wood veneer, from leather to rubber, from discarded packaging to refuse...

This manner of working led to the creation of new textiles, for which she gave no priority to the blend of materials, and she still doesn’t, but instead sought a balance in terms of warp, weft and density. New structures emerged. In her design process, feeling and intuition come first, not the functionality of the fabric. The design process begins with the input of a blend sequence into the computer, which is then transferred to the loom and weaving commences. I can assure you that a loom is frighteningly complex, even with ordinary warp threads and a single weft, but Martine adds a further twenty-four shafts and then it becomes really complicated. Eventually it is the computer that decides how something is woven, at least that is the objective, although Martine continues to make adjustments during the weaving process. A kind of dialogue exists between the computer’s design and the resulting woven expression, a communication between loom and computer, via Martine. Sometimes the woven result of the computer’s design is surprising and unexpected.

‘A thread has its own character which translates into structure and tension. This only becomes visible at the moment you weave a sample. The computer cannot calculate these properties, so my design approach requires real intuition’, she says, ‘you only see the blend and accuracy at the moment a textile comes into being before your eyes. It’s the only way.’

Our textile designer works with a Dobby loom, another name for a computer-driven shaft loom that is different from a Jacquard loom, although only one tenth of the weavers use a Dobby loom. With such a loom you can’t do everything. A designer is limited by the loom’s technique. And, although millions of blends exist, one particular textile requires one blend to make it different from the others. The most suitable fabric for a particular application is determined by the correct blend, appropriate density and right choice of yarn.

In order to find answers, Martine as always carries out research. She visits a weaving mill, chats about the product, the specialization of the mill and its materials. If the latter does not exist, Martine brings new input to the company. ‘Free creativity is necessary to invest in design. Otherwise you limit yourself and you create nothing new. Starting from a dream, a gut feeling is essential’, she says. ‘The textile world is a closed world in which technicians and designers formerly lived and worked separately. Today there is more openness and more collaboration between the two. Bringing excellent technicians together with good designers, and preferably from the very beginning, is crucial.’

In today’s world, you also have to know how to communicate, to go out and make a name for yourself, and Martine is convinced of this. Trade fairs are the best means to that end. Visiting yarn fairs is a must for Martine. It is truly amazing how much yarn is still made and it remains the matière première of her fabrics. You should also go abroad, since the weaving industry in our country has declined. Italy, with manufacturers in Milan and Florence, for example, is very important. But Martine rarely travels outside Belgium because she works for renowned firms such as Van Maele (B), Fibertex (B), Hunter Douglas (USA), ELITIS (F), Verjans (B), Copa (B), etc. Self-promotion does not sit inside her, although winning the Van de Velde Prize in 2000 certainly opened many doors and gave her more self-confidence.

Ulf Moritz, the renowned textile designer and trendsetter, for whom Martine occasionally works, has ‘great respect’ for her as his latest Martine Gyselbrecht catalogue clearly states. She deserves it, just as she deserves her Henry van de Velde Career Award. I, we wish her much fame and fortune in her continuing career.