de Velde

André Verroken

In the context of the first Triennial for Design in Flanders in 1995, we identify André Verroken as a key figure, not only because he's the unique furniture designer who has continued to produce since 1968, but especially because he has been creative and innovative in developing discipline up to the present day.

We could situate Verroken along with his peers i.e. Emiel Veranneman, Pieter De Bruyne, Frank Declerck, Frans Van Praet and others. Less known is the Flemish furniture designer trom Brussels, Jan De Smedt (1929-1982) who taught Verroken a lot. Other important persons are Rudi Vereist, an industrial designer who emigrated to Canada and the reclusive Ludo Verbeke, who now and then creates minimal pieces of furniture. Given the limited scope of this article however, we are unable to examine the work of these people in greater detail.

There was little new happening. After that date, a particularly fascinating generation appeared who started growing from the mid-eighties onwards. In Flanders, the only designers working in a constant and inventive manner as a pure furniture designer during the period 1980-1995 was Verroken. He considers himself as being someone who discovered his 'vocation' rather late in life, although he set up his own office for interior design in Schaarbeek and, for years on end (1971-1982), he worked as a free-lance designer for the furniture factory N-Line International in Kluisbergen. From 1980, his creations and the ideas behind them are gelling stronger. Furthermore, he has remained faithful to his artistic principles throughout those years.

In 1979 he received a grant from the Ministry of Culture that would enable him to continue his experiments in furniture. This was to be a milestone in his career, since it meant that the Commission For Plastic Arts at that time appreciated the strong artistic dimension in his work. Up until then, he had already designed a great deal of pieces of furniture, such tables e.g. the Piramidetafel (Pyramid table, 1973), Octet (1974), Vlindertafel (Butterfly table, 1976), the dinner tables Duo (1978) and Kwadraat (Quadrate, 1979), which already showed a degree of stylistic continuity. This style is rooted in geometry and architecture, in the constructivism that he got to know through the deceased painter Marcel Henri Verdren with whom he worked at the offices of 'Les Architectes de la tour du midi' (The Architects of the South Tower') in 1968 and with whom he had a very intense friendship until he died (1976).

In the mid-eighties, his ideas on 'modules' and 'super positions' for instance were given explicit form. Before 1980, most of his furniture had been tables constructed as harmonious compositions of simple lacquered geometric volumes. On these simple forms, he placed a transparent sheet of glass, thus rendering their construction and interplay between the colour and the shapes of the furniture construction visible and thereby allowing them to interactwith the surrounding space. He also creates industrial furniture, but our main interest however, is in the furniture which are his sharpest expressions of his most refined notions of form. And with these creations, he remains himself among trendy and or critical movements within interior design.

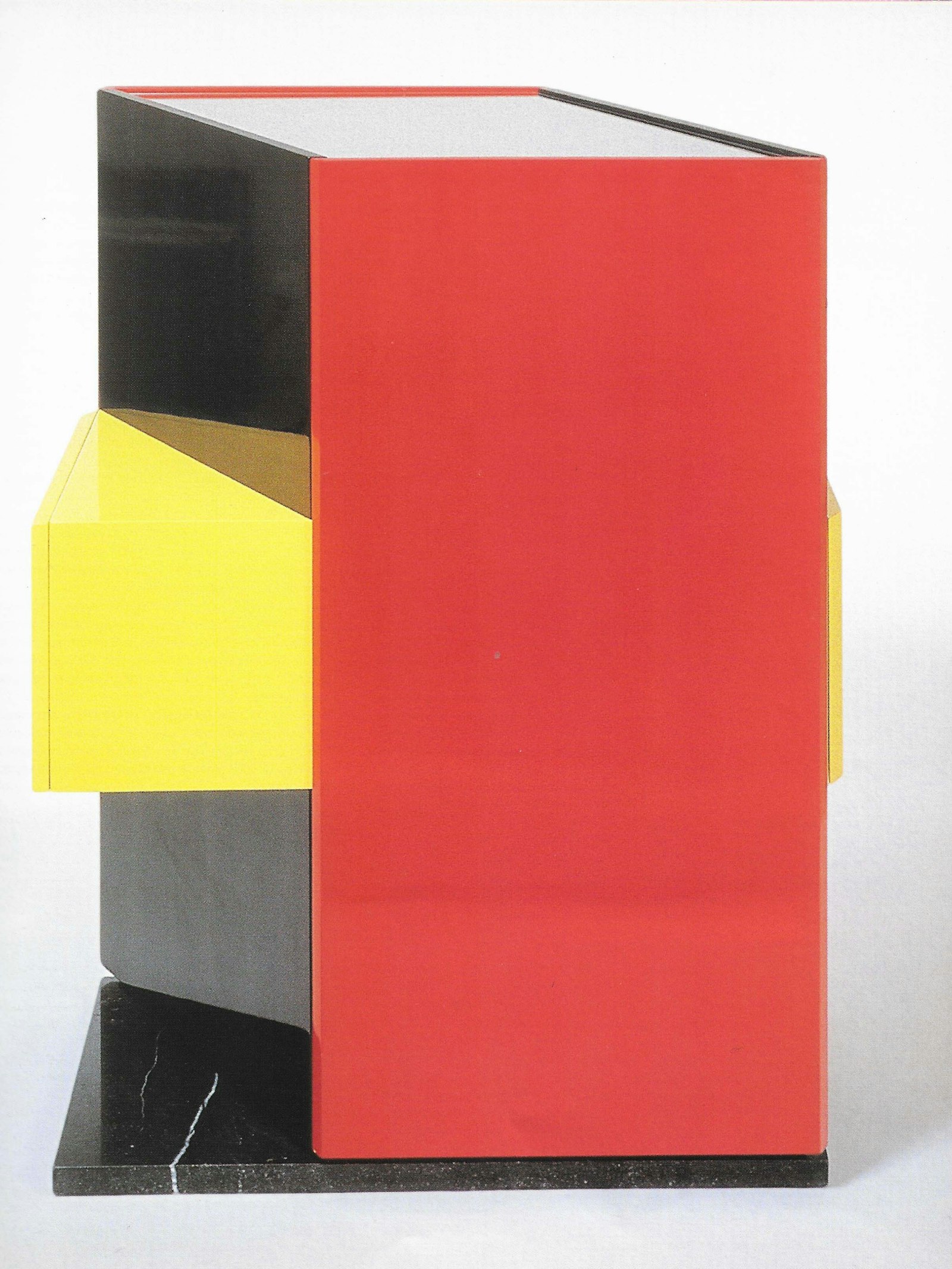

An outstanding example of this is his cupboard entitled Sweet Belgium (1980), created in 1982 in MDF, in which he applied black, red and yellow satin glosses, finishing off the work with mirror glass and bluestone. The colours of the cupboard eluded to the Memphis trend, while its form was inspired by the work of the two godfathers, Veranneman and De Bruyne, of contemporary furniture design in Flanders. On closer examination, one can clearly distinguish Verroken's inspired mark. Sweet Belgium is a geometrical cupboard in which the notion of 'super position' already takes shape. In this sense, it is the precursor of 'Stapeling' (Superposition), which he was to create tour years later. In 1988, his work was given pride of place for the first time at the VAB-VTB exhibition in Gallery XXI in Antwerp. lt represents a move towards his Trapkast (Stair cupboard, 1988), a storage cupboard in black varnished ash wood with a laminated white plate finished with rubber and polished steel, and the Duizendpoot (Centipede, 1988), a cupboard in black ash wood worked with mirror glass and stainless steel, containing six drawers on telescopic rails.

This gained him a great deal of public interest. His pieces of furniture were well received. In fact, Verroken has succeeded in creating a form which was timeless and free. A quotation from 1984 gives in our opinion a correct summary of what he was doing then and is, in tact, still doing today: "The elements and compositions used, which reoccur time and again in my work, allude ( ... ) to that which al ready has been conceived and produced in the course of history. This has nothing to do with nostalgia; all I am trying to do in my designs, is to restore and perpetuate the continuity of architectural tradition. I try to make use of images trom the past, archetypes and existing geometrical figures in such a way that I arrive at my own personal vocabulary ( ... ) I am always in search of a thing's most pithy form.''

He always explores the artistic side thoroughly and places the functional in a larger context. On top of this, there is the aesthetic aspect about which Verroken says: 'Although I consider beauty to be a relative notion, my work can certainly be called aesthetic. This, however, is the result of the great care given to matters of design: ingredients such as proportions, rhythm, material and construction, symmetry and articulations are all given the attention they deserve.'

Verroken continues his search for the simple and pure form and in 1989, he assembled the Booker-prize, a bookcase in satin glossed MDF and multiplex birch. lt is literally a superposition of elements of two different and interchangeable heights. On first sight, it seems chaotic and disorderly: the opposite of what one might expect of a bookcase. On closer examination however, its strict symmetry, geometrical construction and mathematical order emerge. lt has even been reviewed in the fameus ltalian magazine Domus. An interesting feature of this piece of furniture is its minimal handling of the MDF, which is even more striking in his table series Duo, Trio, Ouartet, Quintet, Sextet and Octet. They set off space and all had the basic form of a cube. Each table consisted of two or more cubes connected to each other. All the measurements and thicknesses used were a multiple of three. The musical quality of this repetition inspired him. During the exhibition at the 'Brakke Grond', they evoked a feeling of paradox: extremely pure, simple and common on the one hand, yet simultaneously balanced, perfect and elitist on the other.

In 1994, Verroken exhibited at the Veranneman Foundation. He also put his drawings on display there. Throughout his career, Verroken has developed as a plastic artist. His drawings are directly related to his pieces of furniture. They are constructivist, at times decorative, yet mainly monumental. He showed the 'solidified' version of the Duizendpoot(Centipede), designed in 1988, but only built in 1994 in MDF, solid beech wood and natural varnish. In 1994, André Verroken received the VIZO Henry Van de Velde Award tor the 'Best Product'. lt was attributed to him tor his table Homenaje a Eduardo Chilida. lt is a dinner, working and conference table designed in 1993 and built in 1994 in MDF, finished all aroundwith a lacquered veneer of Indian rosewood and ash. He says the following on the subject: 'Between the shapes and the empty space, between the wood and the air, there exists a relationship which can hardly be expressed in words, but is experienced through the eyes and the emotions. Never before, have I experienced such a strong relationship as during my first physical confrontation with the work by the Basque sculptor Eduardo Chilida'.

Verroken is fond of communicating through his furniture. He dreams of the balanced, pure and clear, devoid of all confusing and depressing features; art that has a soothing, peaceful effect on everyone working with his head - businessmen or intellectuals. Something like a cosy arm chair in which one can relax. In 1995, Verroken created Kontener, another adaptable and superposable programme in the series. In the "International Furniture Design Competition" in Asahikana (Japan, 1996), he won a bronze Award with it.

Also in 1995, there is Loflied aan de architectuur (Ode to the architecture), which is an adaptable composition that can be expanded in height and width. The ghost of Martin Visser who he got to know at the end of the sixties within Spectrum in Bergeyk (the Netherlands) is clearly visible. The creation consists of different sorts of units, a kind of telescoping racks that bend less because of the weight of the books.

In 1996, he creates a piece of bar furniture as part of a series which wasn't finished because of budgetary reasons. In 1997, Jan Hoet ordered a meeting table, a variation on Chilida table, for the brand-new SMAK. lt is more monumental in spite of the profile simplification. The table is six metres. In 1998, André creates a table which is suitable for two to ten persons. In that year, there is a little black table with the title Une table peut en cacher une autre (A table can hide another one), on which a double folded wooden top rests that is twice as big (Sarah De Keuster, 2000). In this sense, it is been set tor two to ten persons. lt is a creation which is the key to Tafels van vermenigvuldiging (Tables of multiplication), which he creates tor the one-man exhibition in VIZO in May 2000. All tables are composed of the combination of at least three base modules which are connected to each other and which can be square or orthogonal. Together they can live a life as table.

In 2001-2002, he finally creates the Kasten van vermenigvuldiging (Cupboards of multiplication). He unravels the table components, takes the different components out of their correlation, changes the components with each other, rotates, overlaps and shifts and brings all this together to a new image. Some cupboards are veneered with two wooden sorts, which contrast with each other. In this sense, the underlying manipulations are disclosed; the story behind it becomes clear.

During 2002, Verroken again introduces lacquering. lt has been a long time that lacquer again became a metaphor. A metaphor that needs to be discovered by the spectator. I feel it as a dematerialising of a three-dimensional object. Because of this skin of lacquer, the object becomes almost intangible, inviolable.

Nevertheless, his furniture becomes less and less consumption-oriented. The creation becomes more artistic and is averse to compromises. This is an Award for a career which hasn't come to an end yet, but which offers a future perspective, worth.