de Velde

Philippe Neerman

For the very first time, the VIZO is giving its "van de Velde Career Award" to an industrial designer pure and simple: Philip Neerman.

This is the logical outcome of the strategic reorientation this Flemish governmental institution has subscribed to. Philip Neerman is receiving this award - a mark of not only our own appreciation, but also that of the whole Flemish Community - for his impressive achievements. Designers of the same age with a similar record of service are incredibly thin on Flemish ground.

Fortunately, the future looks brighter in this field, as a number of particularly interesting designers have emerged in the last twentyfive years. We are thinking of Paul Verhaert and Axel Enthoven, who, although they are in fact still pioneers, have already proved that their design offices belong among the very best, and of numerous young industrial designers such as Clem van Himbeeck, Paul Bailleul, and Marc De Jonghe, to name only a few. Philip Neerman's name had been familiar to us for a long time already, thanks to lnterieur and the former NHIBS, but not his work, because, until recently, we were not really geared towards industrial design. On the occasion of the "2nd Triennial of Design in Flanders", when we made our real entrance into this absolutely fascinating world, his company IDPO (Industrial Design Planning Office) clearly stood out from the rest.

As we had to make a selection from the company's great number of designs, we focused on its solutions to mobility problems, such as the Brussels Underground, which is IDPO's speciality. In Neerman's brilliant record of achievements, the large number of projects for large French cities is striking. On the whole, Belgian clients - except for the bus company MIVB - are conspicuous by their absence, though, of course, our country does not count all that many potential customers in the field of public transport. There are the NMBS (the Belgian railways), De Lijn (local bus transport), and MIVB (local transport), and that is about it. And then we have not even mentioned the stepmotherly treatment which public transport has often been given in the past.

Fortunately, Neerman is highly appreciated among specialists, witness his professorship in Applied Ergonomics at the former NHIBS (National Higher Institute for Architecture and Urban Development, later renamed the Henry van de Velde Institute, and today the Antwerp College of Advanced Education, Department of Product Development"), which lasted for nearly a quarter of a century (1972-1995), during which hundreds of product developers "passed through his hands". We would not hesitate to say that he taught his people how to develop products. Another parameter for his renown in the world of design is, of course, his long-standing membership on the Board of Directors of lnterieur, from 1970 up till the present day. Philip Neerman's career rests on a solid footing. He not only studied at the Brussels Academy of Fine Arts but, even more importantly, also at the famous La Cambre institute (founded by Henry van de Velde in 1927).

His teachers there were the very best, and included Jespers, Navez, Pompe, Francois and Bourgeois. Among his fellow students were the Dhaeze brothers, Michel Olyff, Serge Vandercam, Alechinsky, Pierre Caille, and Dom Grégoire Wathelet.

Following his studies at La Cambre, he started working for Jules Wabbes. He spent one year (1953-1954) with this now nearly entirely forgotten, but uncommonly interesting designer (Mobilier Universel Jules Wabbes). Next, he was recruited by De Coene, the almost mythical furniture manufacturer from Kortrijk, first as a Planning Manager and later as a Product Manager. He would stay there for 13 years. Working for De Coene was much more than an experience, it was like a dream come true. There, he could practise what he had learned, and more. In this period, he designed his furniture for Decoplan, which he was allowed to launch under his own name. De Coene gave him an opportunity to work alongside renowned designers such as Gio Ponti (production of a bathroom), Marcel Breuer (in 1960, studies for the restaurants and the hairdressing salon of the Bijenkorf store in Rotterdam and for the conference halls and libraries in Paris), Saarinen, and Le Corbusier.

Being a member of the ICSID, he also came into contact with other major designers such as Neutra, Bertoia, Pollock, and Charles and Ray Eames. But when De Coene was taken over by the Generale Maatschappij, Philip Neerman left the company and founded his own office which, three years later, became "IDPO" PVDA. During his first three years as an independent designer, he developed a heterogeneous collection of objects, ranging from chairs for Philips and the Royal Library (1966) to radiators and boilers (1968-1971), products for Eternit (1969-1970), furniture for Meurop (1969-1976), an outboard motor for Outboard Marine (1969), lamps for Philips (1970-1971), a conference table for the Brussels Congress Palace (1971), etc.

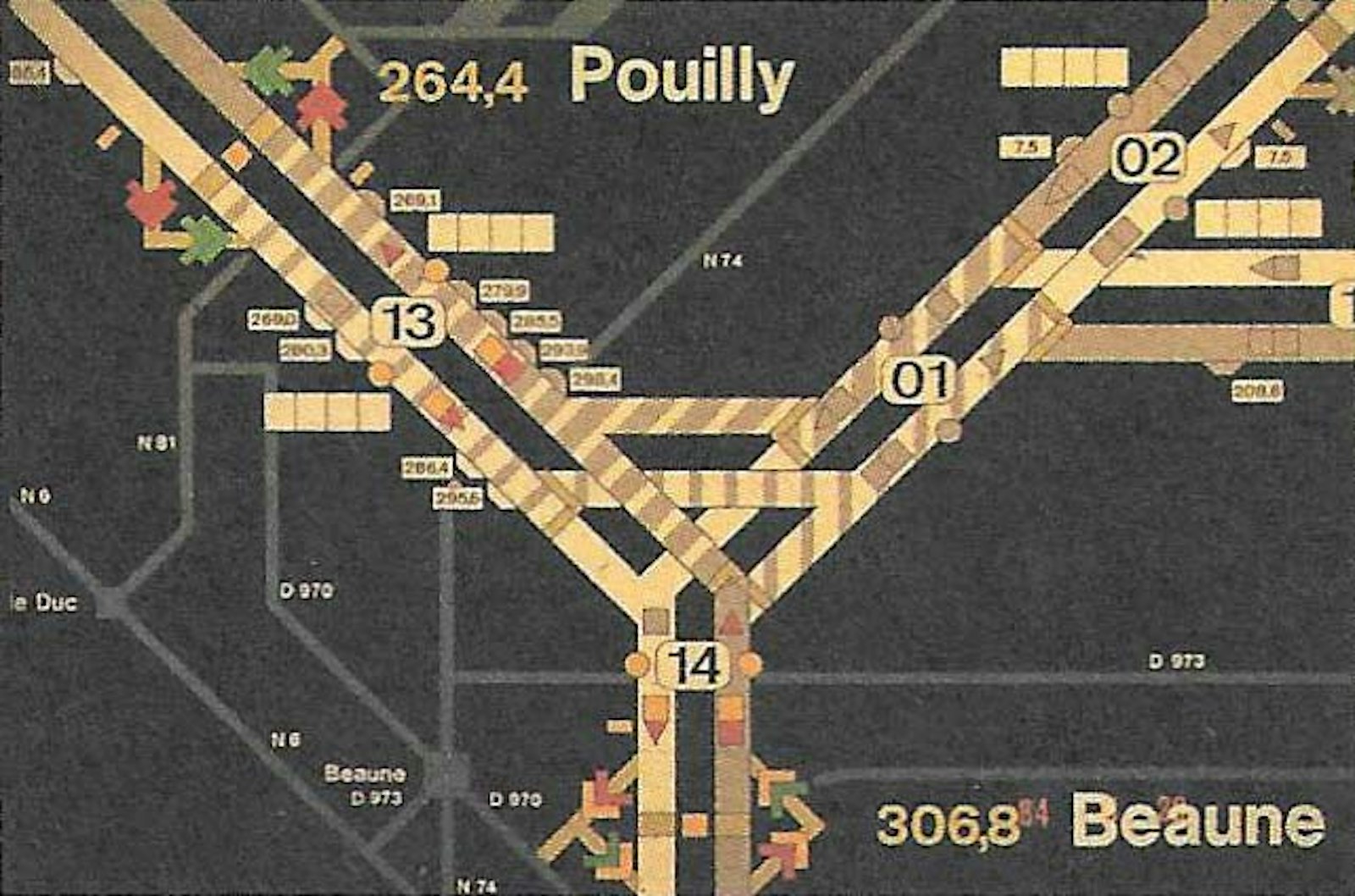

But when he received his first assignment for the Brussels Metro in 1969, he slowly but surely turned a new page in his career. After 1971, he steered away from the study and development of one-off products and the emphasis clearly shifted towards the development of coaches, trains, trams and, above all, tube trains and transport control systems. It all started with the assignment from the MIVB, which brought his company into contact with the transport companies of Lyon and Marseille. These French cities were not inclined to work with Paris designers, because they wanted to take a totally new approach. IDPO had shown it had the innovative spirit and inspiration they were looking for and so it got their orders. IDPO's approach was ingeniously simple. Neerman produced public transport for humans. And he still does. Before, transport had mainly been designed by engineers, who worked from a technological viewpoint and, if possible, for eternity. Neerman was more down-to-earth. His tube trains were - and still are - made for you and me, starting from a total approach and based on principles of applied ergonomics. This total approach implies that, whenever possible, each part of the rolling stock was designed taking every aspect into account: ergonomics, materials, look, psychological effect - in short, everything. It would be a nice idea to set up a design exhibition with two train carriages.

One complete in all its glory, splendour and complexity, and the other showing all its parts with a full explanation. IDPO's approach is necessarily complex. First there are of course the drawing, the studies, the first scale models in cardboard, the more final models in sturdier materials, and finally, a full-scale model before the decision is taken to produce it. It easily takes years to arrive at this stage. A list of design assignments may perhaps not make for the most fascinating read, but in the case of this record of achievements, we would like to make an exception for the following list of transport-related achievement.

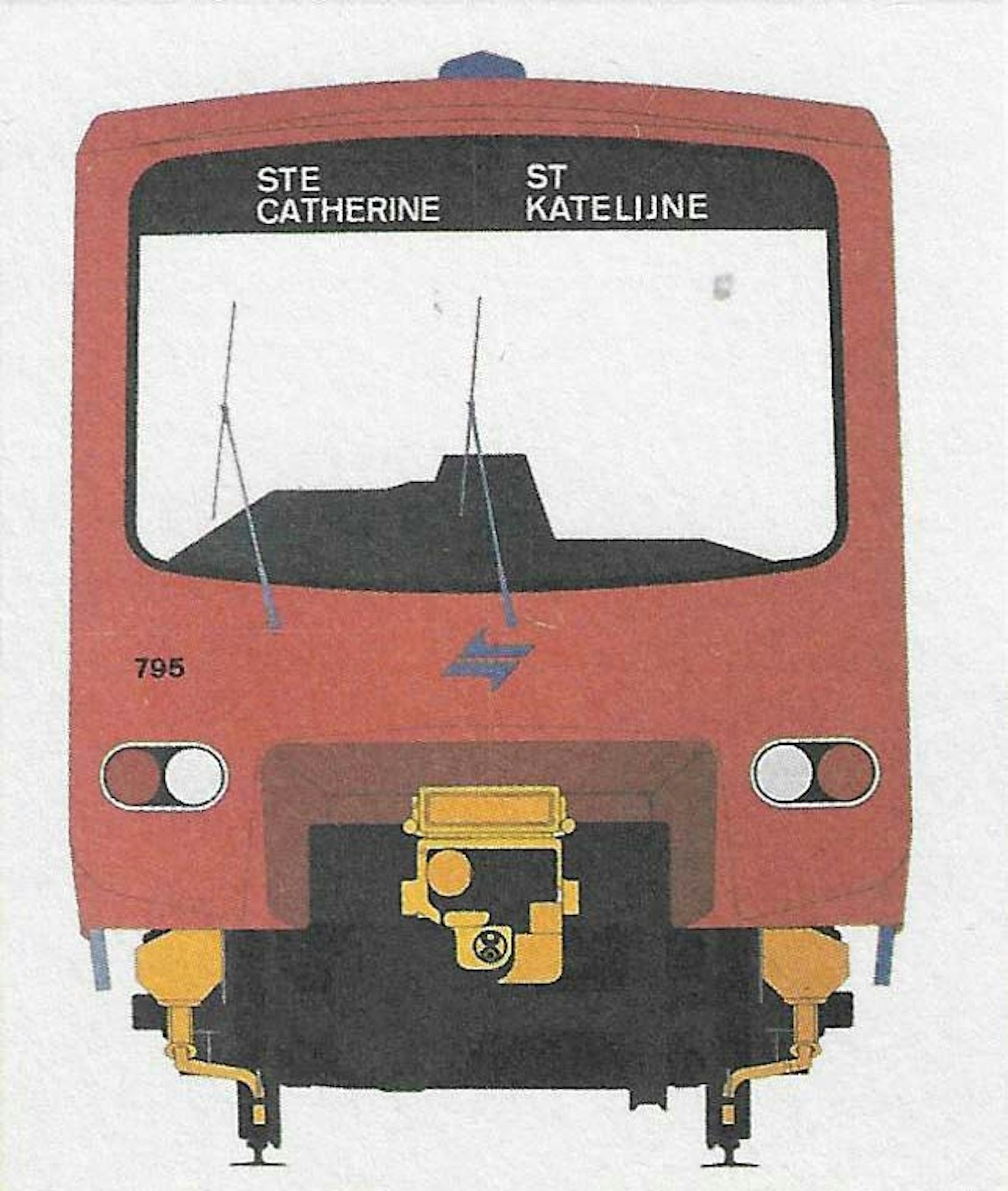

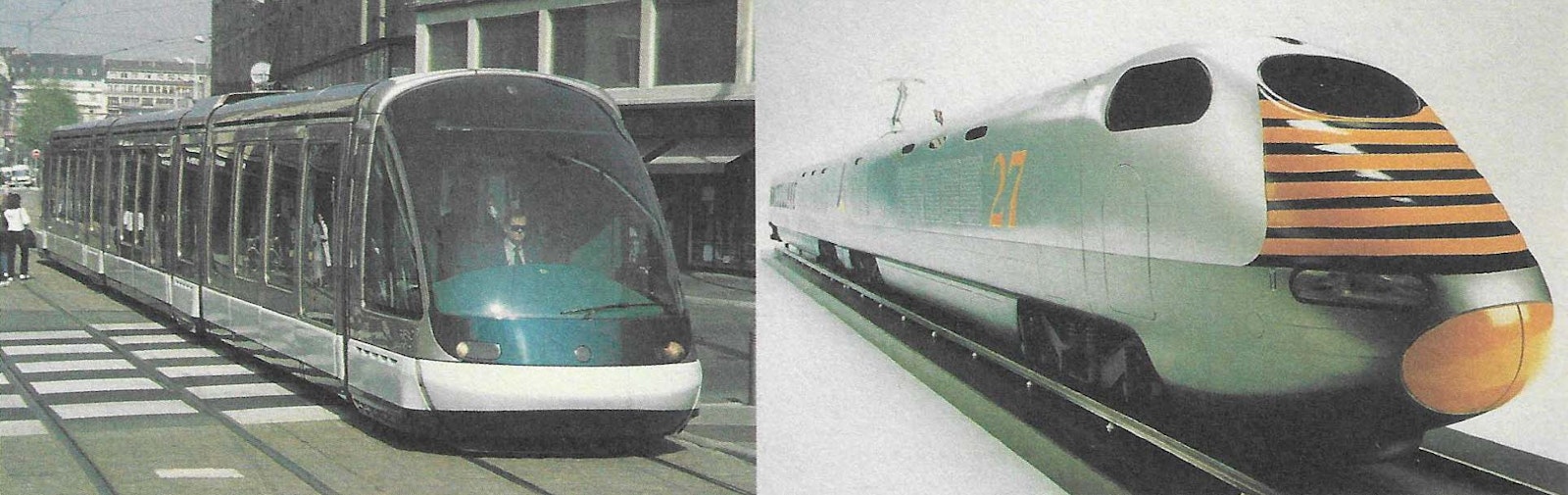

The first train for the Brussels Underground was ordered in 1971, but we had to wait until 1975 before the first train rolled over the rails. In the end, five series were produced, which meant that the assignment was not completed until 1996. For the city of Lyon, IDPO designed an underground carriage (1973-75), an underground with a rack railway (1980-83), and an automatic underground (1984-94). Neerman's underground for the city of Marseille was constructed between 1973 and 1975. Also in 1975, he made a conceptual study for the Paris underground (1975), for an "R.E.R. interconnection" (1974) in Paris, and, in besides a number of other assignments, for a redesign of the French TGV (1986). In addition to underground trains, Neerman also designed tramcars.

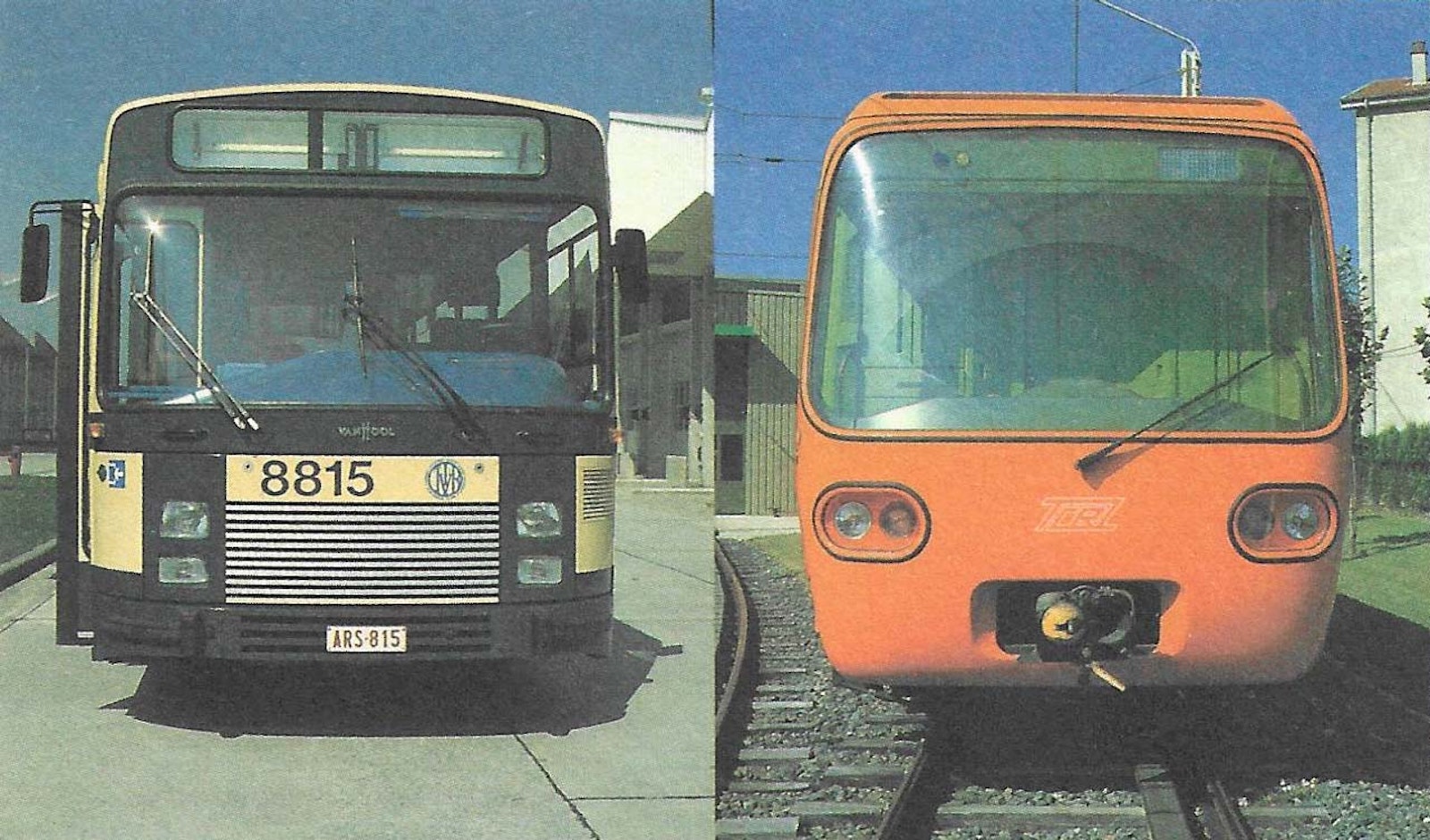

In 1975, he designed a standard tramcar in collaboration with Brugeoise & Nivelfes and Matra. Next, he designed trams for Amsterdam, The Hague (both in 1976), a limited design for Philadelphia, a double-deck tram for Hong Kong in 1977, Nantes (1978-80), and standard trams for Grenoble (1983-1993) and Strasbourg (1986-1995; 1998), in two series. There was also the development of a light urban transport system and a totally new tram range for Citadis in 1995, which was finally taken into use in 1995 in Croydon (GB), in 1996 in Dublin (IRL) and Porto (P), Stockholm (S), Clermont-Ferrand (F), Montpellier (F), Orléans (F), in 1997 once again in Nantes and Lyon, and finally in Bordeaux in 1998-99. Other important assignments were the development of the Eurostar in 1988 and the Shuttle train in the Eurotunnel under the Channel in 1990-91. For Neerman, this was one of his most special projects because these carriages were very large. They not only had to transport trucks and cars, which demands totally different criteria than passengers, but there also had to be a second floor, with a refreshment bar of sorts, where the travellers could relax.

He also designed coaches and trolleys, some of which were articulated, for which his main Belgian customer was the MIVB in 1972 and in 1981-83. Of course the French cities once again bought the lion's share. IDPO developed a trolley bus for Lyon (1991-92), a new look (1990-92) and a coach (1993-96) for Strasbourg and recently, in 1997, a preliminary study for a range of modular city coaches, once again for Lyon. By the end of the eighties, he ventured to design rolling stock on funicular railways, most of which — you might have guessed it by now — have been installed in France. Yet the office is polyvalent and does not only design carriages but also systems. Examples are the funicular of La Grande Motte (1988-92) and the development of Systeem SK, an automatic city transport system for short distances. His latest project in this field is the design of the SK cabin for Roissy-Charles de Gaulle airport in 1992-94.

Concepts and projects on contemporary transport issues are not limited to the conception of new carriages, but also imply the development of work and control units. These products in their turn are not limited to transport on rails, but also imply road transport. They are less user-oriented, but very important for the safety and comfort of the travellers. But Neerman would not be Neerman if his design of these systems did not take the ergonomics of the steering cabins and control centres into account for the people who work in them. Ergonomic studies are at the basis of the concept, and this shows in the synoptic control panels and all other equipment of such work posts. Naturally, IDPO started specialising in these installations from an early date (1975) and is still a top office in this field. And once again, France has been the most important buyer of these studies and projects, although, in 1995, the NMBS ordered a project for central working posts. This concerned an ergonomic study of signing posts and the future traffic co-ordination centre.

His architectural realisations are less known. We will go over them briefly. In 1963, Neerman did the interior design of the Brussels Design Centre together with the architects Brodzki and Génicot. For the Royal Library of Belgium (1967-80), Neerman collaborated with the architect Roland Delers for the realisation of the museum halls, the public signposting, the offices, the conference hall, the exhibition hall, the donation cabinets of Solvay, de Gelderode, de Launoy, Verhaeren, and Hirsch, the Valuable Documents Room, the Print Gallery, and the Coin and Medal Room.

The restoration and the interior decoration of the halls devoted to Charles of Lorraine are also on his list of achievements. Other important assignments are the global decoration of the Royal Institute of the Art Patrimony (1962-82), the Royal Palace (1975-76), the Brussels Audit Office (197882), and the Royal Palace in Laeken (197883).

Philip Neerman himself is particularly proud of his share in the realisation of the Brussels Museum for Musical Instruments (1982-1998). This project, in collaboration with the architects Bontinck and Gus, encompassed the realisation of the complete structural works of the new museum buildings, the renovation and restoration of all existing buildings composed of Old England and Saintenoy, on the Place Royale. The interior decoration and permanent furniture also passed through the hands of IDPO, as well as the concert hall and the recording studios (1998).

This "VIZO van de Velde career award" is not Neerman's first award. He already received a number of awards such as the "Louden Industrieel Kenteken" (1960) for a sanitary range designed for the company Weydts, a "Gouden Penning" (1964) at the Milan Triennial for a telescopic stage, a "Zilveren Penning" (1964) for his furniture range Decoplan and the IF Product Design Award (1998) for the "Citadis" tram car as "Excellent Design". Our "van de Velde award" is therefore well-timed. Fortunately, Johan Neerman will succeed his father in the business. He is an architect and has already received his first award, the silver plaque of the Provincial Prize of Industrial Design of the Province of West Flanders. But even more important is the fact that he shares the views of his father, who is less interested in the engineering aspect, but rather in the intrinsic value of the cultural component of his projects. Neerman still likes to be called an artist. He regrets the emphasis on exact sciences and the "engineering trend" in the design courses in Flanders. In his opinion, industrial design is cultural and, in its own way, even art.

Philip Neerman most certainly deserves his place in the gallery of the Design Masters of Belgium.