de Velde

Sofie Lachaert

In 1980 there was a significant exhibition of contemporary jewellery in Temse. It had the title of Atelier 35 and was the first of its type to show work by fresh, young and innovative precious metal workers.

Sofie Lachaert pushes boundaries, but not alone

Prior to that Belgium had – bar the jewellery experiments of a few sculptors – been a non-entity in the field of innovative gold and silver work. Wim Ibens and later Jean Lemmens were the exceptionally involved teachers at Atelier 35, the jewellery workshop set up by Ibens at the Royal Academy of Fine Art in Antwerp. There they laid the foundations for a discipline that today has resulted in David Huycke’s doctorate, as well as the appointment of two lecturers-in-charge of two very important courses in the silversmiths’ trade: Hilde De Decker at Sint Lucas Antwerp and Nedda El-Asmar at the Antwerp Royal Academy of Fine Arts, now Artesis Hogeschool. As a young art historian I picked up on this remarkable exhibition and fell in love with it. I felt a sense of joy that finally our country, our region, had a generation of trained silversmiths who questioned the concept of jewellery in an open and artistically qualitative way. Daniël Weinberger was one of the participants and back then he was already questioning a lot of things.

In 1968 – that magical year in which a great many things were possible – the course started up on a small scale, but grew ten years later to become a statement in the creation of ornaments. Only that wasn’t the word they used back then. The term was: jewellery. Gold, silver and precious metals were the materials; the circle, the straight line and the square were the geometric design basis. Perspex and non-precious materials were initially frowned on, but won their place in the creation of ornaments in 1983. The ‘craft’ was learned and was one of high standing, but above all there was the opening out of the free spirit of the artist. It was that spirit that somehow broke down the walls of traditional craftsmanship and gave jewellery the opportunity to come of age as an artistic medium. A lot happened in the world of the ornament between the late 60s and the early 90s of the last century. In the Netherlands, Germany and the UK, the ornament was redefined. Silver- and goldsmiths took a fresh look at wearability and value.

Jewellery was magnified to become sculptures, even though, unfortunately, sculpturing doctrine still dominated the new discipline. Techniques of all kinds came and went and were tested in terms of tenability. There were cross-pollinations with other disciplines, such as textile design, ceramics, paper, etc. The gold and silversmith’s trade, which over the centuries had been a decorative, class confirming and stereotyping applied art, stood up and demanded its independence in that time. Jewel became ornament, but served no other purpose. It demanded attention and forbearance from its buyer or wearer, but actually sought to define the bearing of the wearer. The ornament no longer said something about status, social vision or situation, but propounded the vision of its creator, the artist. When you wore the object you were no longer playing a role.

It was in this time that Sofie Lachaert studied jewellery design. Born to a creative family, with a mother in fashion design, and following the obligatory turbulent adolescence, she decided to follow a goldsmiths’ course at KASKA. Sofie didn’t want to do fashion per se, despite having a great grandmother, grandmother and mother who were successful in the fashion world. She found fashion too ephemeral, too transitory.

She boarded at the Heilig Graf secondary school in Turnhout where Paul Bourgeois, a man who brought out the tactile, the poetic in her, was one of her teachers. His charisma amazed her, even just the way he thought. She graduated from KASKA in 1982 and quickly found her way to Design Flanders, then still in the VIZO (Vlaams Instituut voor het Zelfstandig Ondernemen: Flemish Institute for Entrepreneurship). In 1983 I invited her to exhibit at the Strombeek-Bever Cultural Centre, where for the last five years I had been exhibiting the work of fledgling, recently graduated jewellery designers. Back then, her ornaments looked different to the trivial stuff churned out by the commercial gold world, but fitted in perfectly with the designs and ideas of contemporaries from her generation: Pia Clauwaert, Linda Liket, Pascaline Goossens, Daniël Weinberger, later Hilde Van Der Heyden, Henk Bijl, Anne Zellien, etc. The exhibition in Strombeek-Bever was probably one of her first encouragements to take this discipline further, for a year never went by when she didn’t participate in lots of exhibitions, even international ones. In 1986 I set up the first overview exhibition entitled Art Jewellery in Belgium from Gothic to Date in the Design Museum in Ghent, and, of course, it included Sofie’s work. I also took it with me to the Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon in 1987, for an exhibition on contemporary art jewellery in Belgium. In 1989 Sofie had an exhibition at the renowned Schmuckszene ‘89 in Munich, nowadays the world’s leading event for modern ornaments. But Sofie thought nothing of exhibiting in the region of her birth, the Waasland, as well as taking part in renowned events like the Triennale du Bijou in Paris, exhibitions in the Marzee top gallery in Nijmegen, the Ademloos Gallery in The Hague (unfortunately now gone), exhibitions in Japan and much, much more.

In 1990 she came over to my place one evening, at Sint-Amandsberg near Ghent, to talk to me about a new initiative. She was thinking about setting up her own gallery to display the sorts of things to which she could really lend her support and couldn’t really find in the design world around her. She asked me for my advice, or perhaps for a little encouragement to follow this road further. She wanted to exhibit wild, young talents, people who sought to break through time-honoured barriers, and she wanted to support them through this would-be initiative. She didn’t have the money, just the uncompromising desire to do it. I agreed with her, adding that an initiative like this wouldn’t necessarily go smoothly, but was certainly worth the effort. I was amazed by the courage that young Sofie showed in starting out on an adventure like this. The rest is history, though it was a long time in the making.

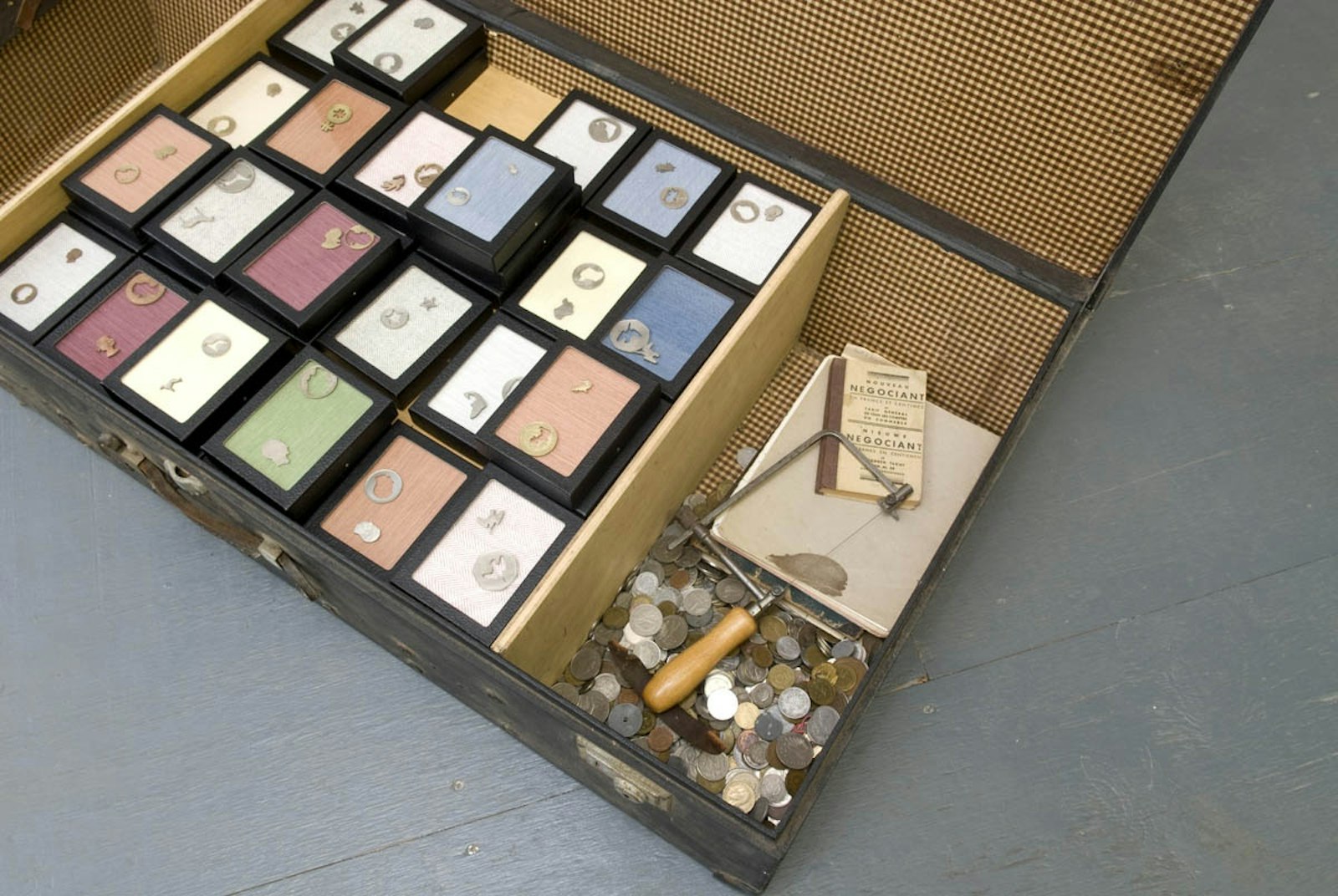

The early 90s of the 20th century were pivotal years in her career. Sofie set up her gallery in Ghent in 1992 and organised the exhibition entitled Le palais sur les vagues (The palace on the waves), in which she showed for the first time her vision of the contemporary jewellery scene. She told the story through a breathtaking, completely new structure. In 1993 I invited her to the exhibition Een schitterend feest (A dazzling feast) which was held as part of the ‘Antwerp Cultural Capital of Europe’ celebrations. It was then that she forged for the first time an object in silver, a three-tiered dessert dish, and this made her start to think differently about her medium.

There was the unsuccessful Antwerp gallery in 1997, which shut down after a while. But it was the opening of the Sofie Lachaert Gallery in Tielrode, in a romantic rural location on the Scheldt, where she now lives with Luc D’Hanis, her husband, that nudged her career in a firm direction. Luc is a painter and on the face of it he didn’t have much to do with his wife’s career, although he was, of course, highly involved and gave her all his support. Obviously he was there all the time, although he never took centre stage. That honour he gave to Sofie. All this changed in the 21st century. As of then, Sofie Lachaert and Luc D’Hanis worked together. Marjolijn Van Duyn, former owner of Galerie Ademloos, wrote: “Life and work are inseparably bound, and ‘sharing’ is one of the themes that run through their work.” Their fate was to enjoy international fame. They came into contact with Droog, a well-known Dutch design collective set up by Renny Ramakers and Gijs Bakker. The part they have played in Droog presentations has not gone unnoticed, certainly not from 2005 to the present day in Milan. It is the fruit of a collaboration between silversmith and visual artist. Design Flanders has kept up its end too and invited them to participate in a number of exhibitions, one of which Je suis dada, was conceived for Turin, the world’s first design city in 2008, and won international acclaim, later travelling to cities including Milan, Vienna, Prague, Madrid, Brussels and even Sint-Niklaas. Lachaert and D’Hanis took part with their legendary sugar pot, disguised as a tiny bird cage. Their stands in the biennial Interieur in Kortrijk were original and inspirational. “In their objects, furniture and installations they try to break down the boundaries between (applied) art and design. Meanings and functions are shifted. With subtle twists they give everyday objects new meaning and recharge them with unexpected beauty.” This line from their CV is as fine a summary of their work as any. They truly deserve the Henry van de Velde Career Award.