de Velde

Koen De Winter

The winner of this 12th Henry van de Velde Career Award is an international industrial designer who was born in Mortsel and is now the holder of a Canadian passport.

He is however one of the few Belgians whose products are exhibited in the renowned MOMA in New York. Koen De Winter (born 1943) has been living and working in Quebec since 1979 and has reached dizzy heights as a designer. He designs products for everyday life from his very socially engaged vision of the world. He is an uncomplicated, open and accessible man, averse to celebrity, who feels the calling to design in the marrow of his bones. Despite an impressive international career he still feels Flemish at heart, even though he speaks French, English and Swedish in Montreal and says his 'Dutch is getting a little rusty here and there' (cit. letter from Koen De Winter, 19th December 2000). However, it is not as rusty as he makes out, for when I met him at the SIDIM (lifestyle) fair in Montreal in May 2005 I didn't notice this at all.

His CV reads like a travel book, like a pioneer's hike through the world of industrial design. The story is one that led him first from Flanders to Wallonia. As a thirteen year old in Maredsous he started his training in ceramics (1957-1962). At that time the abbey school in Maredsous was the top school in Belgium, where, alongside Ter Kameren, crafts and design were taught at a high level, albeit with a firm practical orientation and a view to designing and producing religious objects.

It was the former head of this school Don Gregoire Watelet, famous for his book on Serrurier Bovy, who inspired the pupils to apply a certain creative licence.

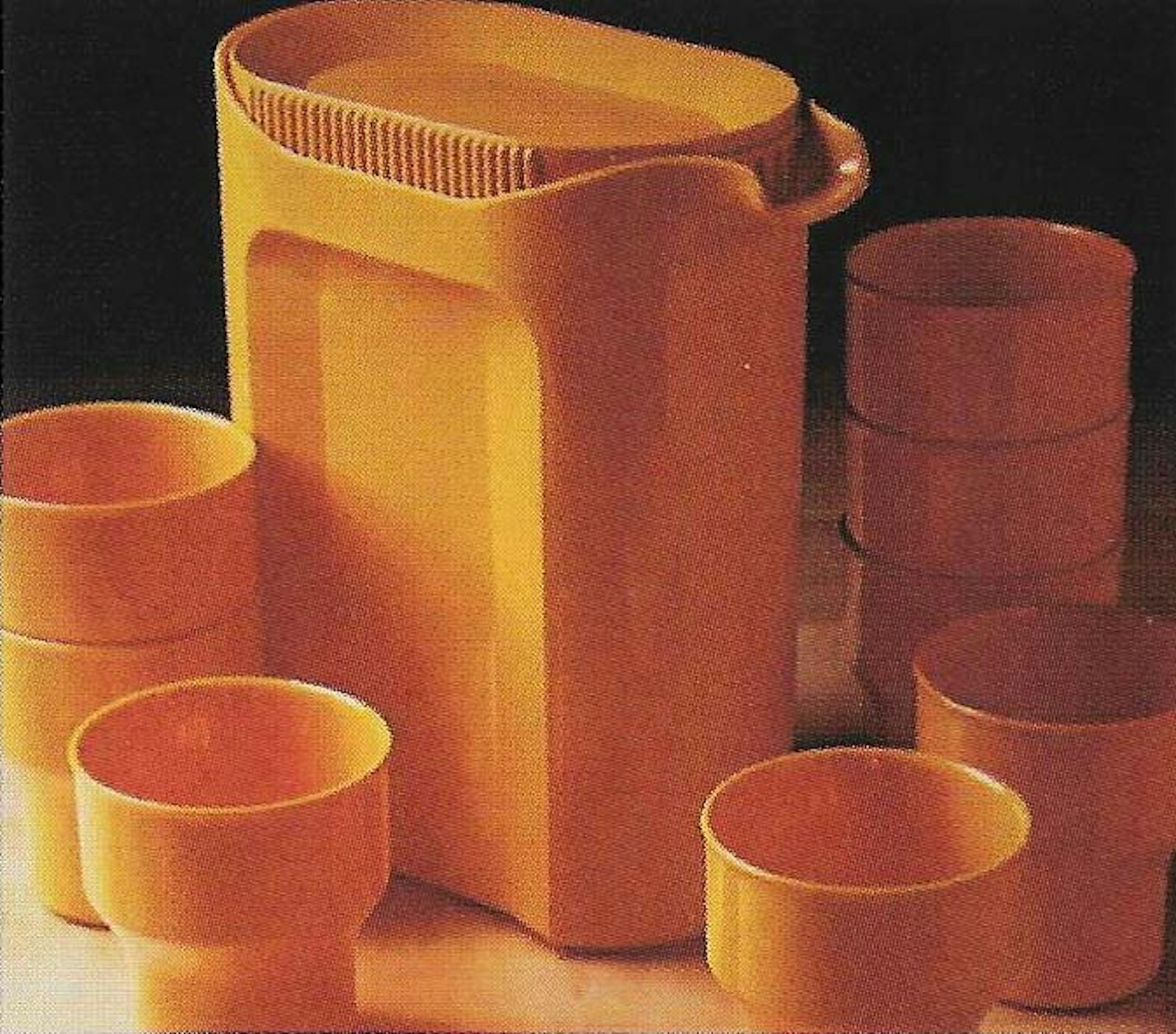

After Maredsous, Koen disappeared into the army, only to resurface in the Netherlands, at the Academy of Industrial Design in Eindhoven. He finishes his studies there with honours in 1969. However, as a student he was already gathering work experience, mostly through trainee placements, in the Netherlands for Shell and Ahrend, in Belgium for De Coene, and back in the Netherlands for Mepal, before ending up at Volvo in Sweden. He married a Swede, and he and his wife went to live in Sweden for a while. In 1971 he was given a permanent job at the Dutch firm Mepal, a manufacturer of plastic consumer goods (household articles, service sets, drinks containers, etc.). Later, in 1977, Mepal became Mepal-Rosti, following the acquisition of both firms by the A.P. Moller group (Maersk Lines).

It was these products that the Museum of Modern Art in New York bought in 1978. Another Mepal product was a set of plastic plates used to serve food to the astronauts in the film '2001: A Space Odyssey'. In 1980, the City Museum in Amsterdam bought the set to add to its design collection.

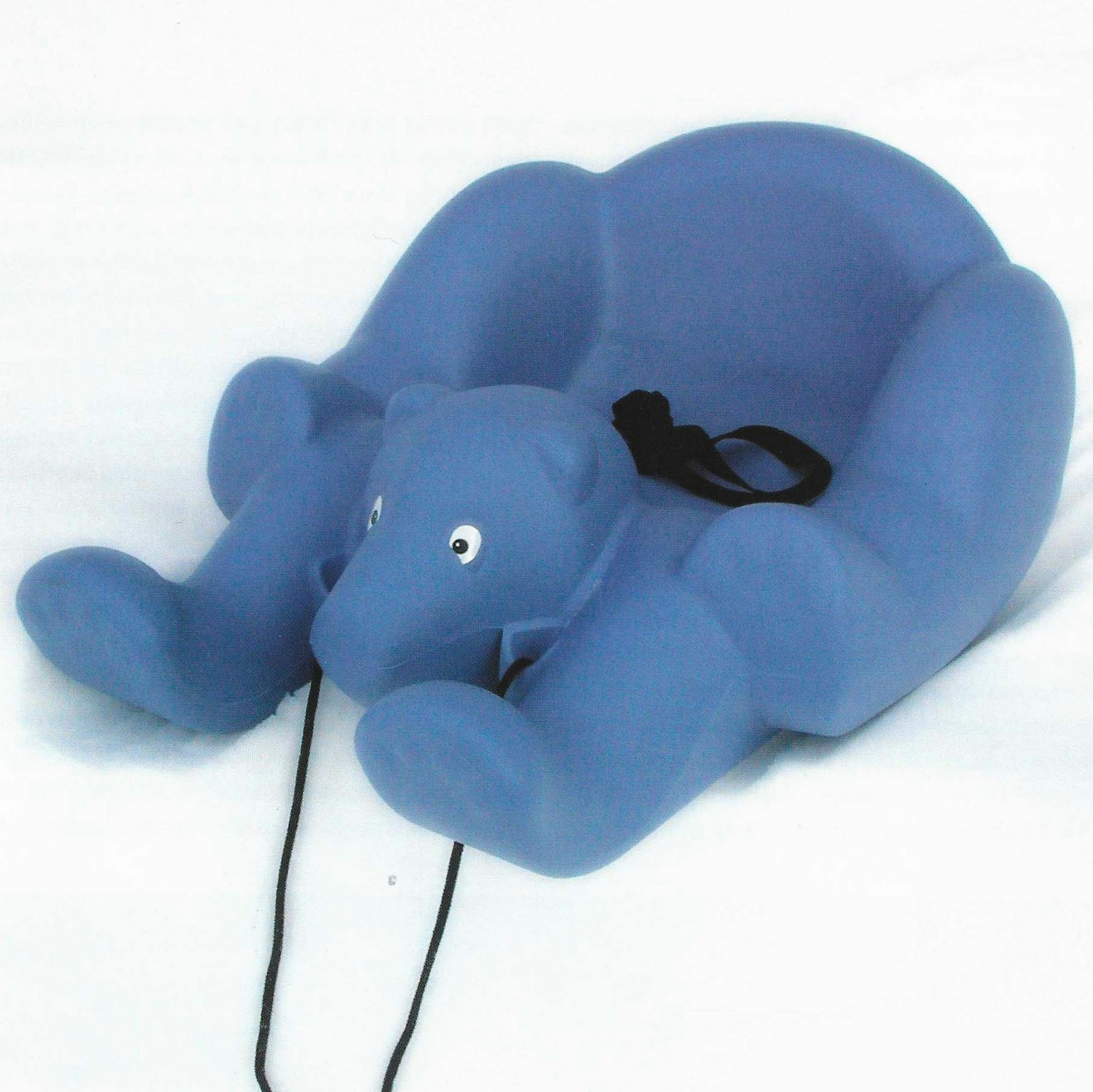

Koen stayed with MepalRosti until 1979, as head of the design department, but left for Quebec, to join Danesco, a maker and importer of kitchen and tableware, where he became vicepresident of design. In Quebec Koen developed his career as a designer to the full. In 1980 he became a lecturer and then, a year later, a professor at the University of Montreal's design faculty. His lectures focused on design history, but also dealt with technology and materials. He stayed on as a professor until 1990 but resigned this position because, despite warning of his desire to step down, he was appointed to the position of director by the faculty board. Attempts were then made to convince him to stay in education, something he himself never wanted to do. In 1989 he had set up Hippodesign, his own design bureau. This choice of name is a story in itself. Koen had no desire to give the bureau his own name, and, since he had particularly good relations with Frogdesign in California, the name of an amphibian or aquatic animal was on the cards. In the end the suggestion came from Enzo Mari, who said: ' ... Well, you know, in the world of design Koen is a bit like a hippopotamus: you don't see much on the surface, but there's a lot of him under the water'.

And the name stuck. Hippodesign was born - a name that is easy to remember, and one with a story behind it. The bureau was set up with the aim of taking mainly young novice designers and giving them their first few years of experience. Hippodesign's operations take in all continents of the world, but are particularly strong in North America. The European firms are Mepal-Rosti, Expanded Holland Belmark, Pianomobil (Antwerp), Bodum, Rhone Poulenc, etc.

Koen De Winter has also been very active in designers' associations, such as the 'Quebec Association of Industrial Designers' and the 'Association of Canadian Designers'. He was even president of both associations for a few years. Particularly worthy of note is the 'Koen De Winter Foundation' into which he poured the majority of his earnings as a professor, seeing as he did not want to become dependent on his income from education. This fund was set up to finance promising students for study trips, exhibitions, publications, etc. It was later given the name 'Bourse Maud Haviernick', in memory of a student who died during the so-called 'Montreal Massacre' at the Polytechnic.

Koen stopped counting his designs when he reached four hundred, as he says himself in his letter of 19th December 2000. It is worth running over a few of them again. A number of his briefs at Danesco were in the area of graphics and printing, such as designs for packaging and logos, but the majority are real products. Looking more closely at his CV, which only mentions patented products, we see a hugely diverse range, from a system for distributing medicine in hospitals (1972), a spaghetti spoon and portion divider (1984) and a halogen lighting system (1993), to a folding table (1995), a soap dispenser (1998) and a watering system for house plants (2003),a few sledges (1999-2004) and cooking pots. De Winter states: 'Hippodesign's biggest customer was always Pelican International. With 325 employees, it is now the largest producer of small pleasure boats in the world. The winter products, such as sledges, are a recent activity to balance out the seasonal character of boat making. We have designed a large number of parts for them, as well as three complete fishing boats, four paddle boats, two canoes, five kayaks, etc. And some of these were after 2003'.

He has also worked for Demeyere in Herentals, the firm that makes high-quality cooking pots. He designed a set with the name 'Sirocco' (1995) and the more recent 'Atlantis' (2000). in which he combines aesthetics and ease of use with the highly advanced technology unique to this company. Clearly, he has made a speciality of cook and kitchenware. A lot of his best designs are in the realm of household articles. Presumably his initial training in ceramics in Maredsous has something to do with this. However, the artistic or traditional crafts are still extremely important to him. He has a distinctly positive opinion on their place in our modern society. In an essay written in 1977 with the title 'Sur le caractere specifique des metiers traditionnels et leur rôle dans notre société' [On the Specific Nature of the Traditional Crafts and their Role in Our Society] he writes in the introduction: 'At the eve of the 21st century, the heritage of traditional crafts and their transposition in contemporary technology still form an important basis for the success of the manufacturing industry.'

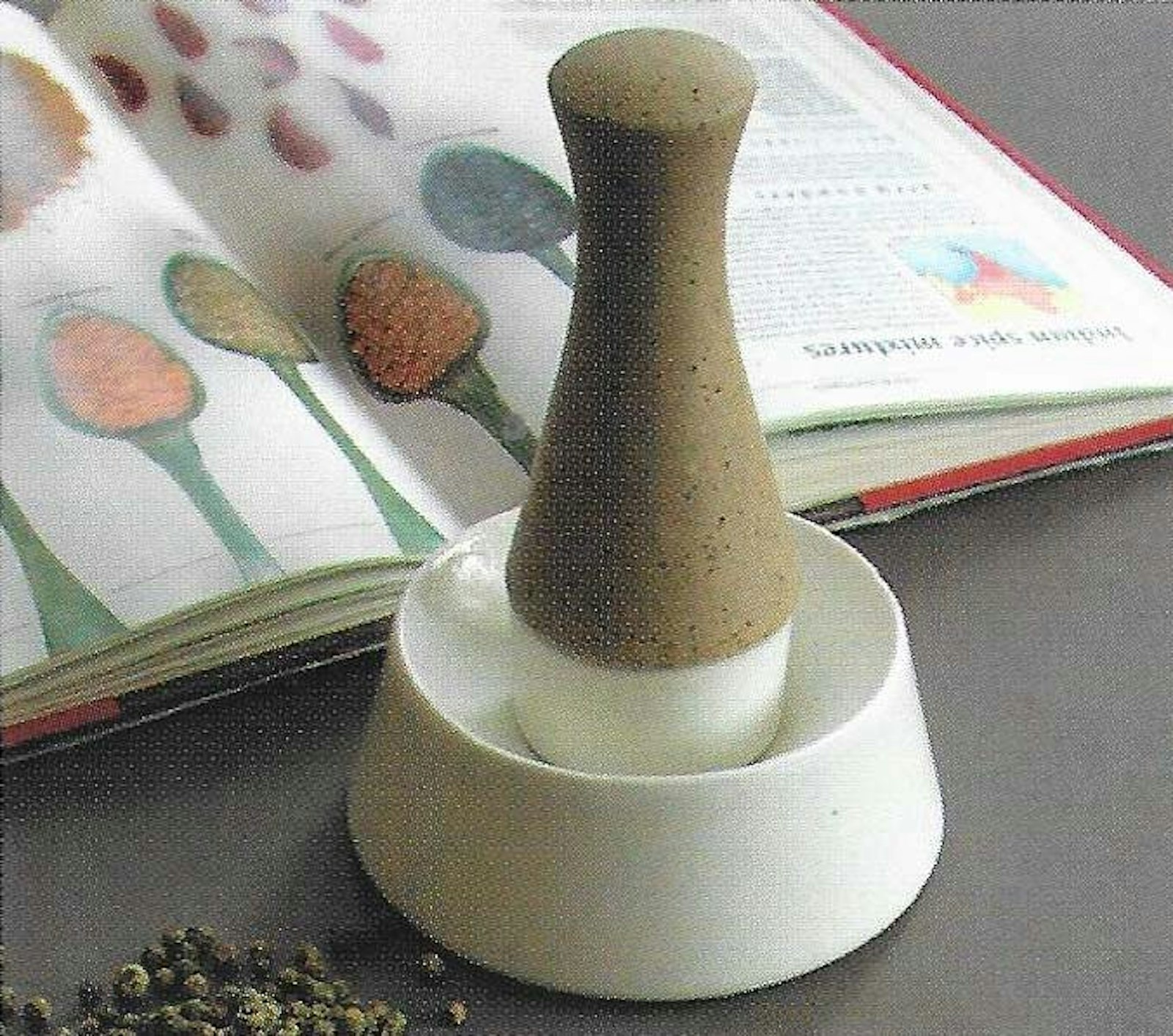

He is talking about aspects of the traditional trades, where it appears that the craftsmen decide not only on the raw materials with which they work, but the techniques, and the form they wish to achieve; and about management, sales, and in brief everything to do with the trade. To him these designers are generalists, who develop certain qualities from which an industrial designer can learn. His small business, Atelier Orange, is completely in line with this philosophy, producing as it does ceramic kitchen products on a small scale.

In Quebec many villages are surviving on the proceeds of lumberjacking, and very often on the comings and goings around this. If this traffic comes to a standstill a village of this type usually disappears. With Orange Koen is trying to restart the economic engine of such a village, Saint-André-Avellin. The mortars and lemon squeezers are cast in porcelain and stoneware. They have an attractive look about them, and work well. The decision to cast is not just about the result they have in mind, but is designed to show the people of the region that it makes just as much sense to produce there as it does in the suburbs of Montreal. Casting is also easier than other clay-working techniques. The nice thing about this idea is that Koen De Winter appears to be rounding off his career where he started - in ceramics.

Koen De Winter has been awarded the Henry van de Velde Career Prize because he is a very complete designer who - as every designer should do - creates simple, useful and high-quality products.